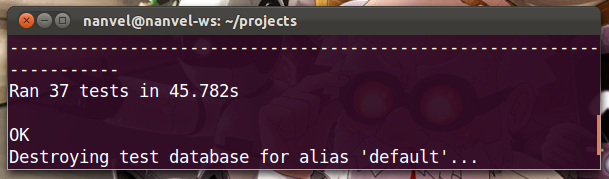

Testing Django applications

Code without tests is broken by design.

- Testing Django applications

- TDD (Test Driven Development)?

- Do I need 100% tests coverage?

- Place for tests code

- Names for tests and TestCases

- Inside TestCase

- Factories

- Using Client

- ImageField with null == False in tests

- Patch/Mock

- Testing models

- Testing forms

- Testing context processors

- Testing middlewares

- Testing template tags

- Testing template filters

- Testing management commands

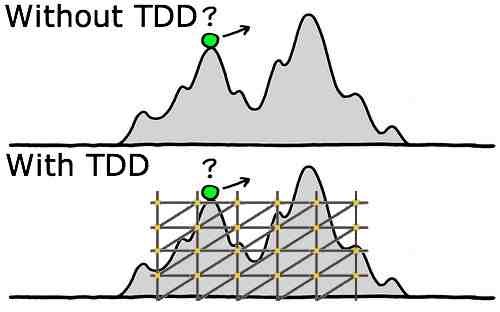

TDD (Test Driven Development)?

The most efficient way is to write tests and feature in parallel, part by part. For example: create url entry, add view and then write test that checks access rights, fix view, extend test to check what view returns, extend view, ...

Do I need 100% tests coverage?

Extreme reliability comes at a cost: maximizing stability limits how quickly products can be delivered to users, and dramatically increases their cost, which in turn reduces the numbers of features a team can afford to offer.

Mark Alvidrez, Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems

Place for tests code

Split tests into files by entity type:

myapp - __init__.py - models.py - forms.py - views.py - tests -- __init__.py -- test_models.py -- test_forms.py -- test_views.py

Prefix test_ is useful when I try to find files with tests in sublime text using mutual search. And this splits tests from tests utils and factories files.

tests/__init__.py have to looks like:

from .test_models import * from .test_forms import * from .test_views import *

From here I want to strongly recommend to use relative imports to refer to files from current app:

+ from ..models import MyModel - from myproject.myapp.models import MyModel

This one simple thing may make your app reusable.

Names for tests and TestCases

I like to use names like this:

from django.test import TestCase class MyAppModelsTestCase(TestCase): def test_unicode(self): ... def test_some_method(self): ... class MyAppTagsTestCase(TestCase): def test_my_templatetag(self): ...

So, if I want to run test for certain app models, I enter in shell:

python manage.py test myapp.MyAppModelsTestCase

I should not remember complex names or open tests file and see name of TestCase, I just remember the rule how to build names.

Inside TestCase

A single test have to assert behavior of a single view, model, form, middlewar, templatetag or function.

If particular code migrates from one test case to another, then we have to use base TestCase class or factories/utils.

For example, create user and login using his credentials. We can place this code into helper function:

from django.contrib.auth.models import User from django.test import TestCase class MyAppBaseTestCase(TestCase): def create_user(self): return User.objects.create_user( username='kanata', email='kanata@mail.com', password='kanata')

Bad thing here is that we hard coded username and password. But, a trick is to use password == username, so password are always available:

class MyViewTestCase(BaseTestCase): def test_my_view(self): user = self.create_user() self.client.login( username=user.username, password=user.username)

Factories

Factories allows to fill models with automatically generated data.

factory_boy is a good choice for large projects.

Another one - dajngo-any.

Example of test without and with django-any:

# example models class Genre(models.Model): caption = models.CharField(max_length=50) description = models.TextField() class Anime(models.Model): caption = models.CharField(max_length=50) slag = models.CharField(max_length=50) genre = models.ForeignKey(Genre) year = model.PositiveIntegerField() studio = models.CharField(max_length=50) last_update = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True) added_by = models.ForeignKey(User) def __unicode__(self): return u'{captions} ({year})'.format( captions=self.caption, year=self.year) # without django-any class AnimeModelsTest(TestCase): def test_anime_save(self): user = User.objects.create(username='user', password='password') user.save() genre = Genre(caption='new_genre', description='description') ganre.save() anime = Anime( caption='new_anime', slag='anime', genre=genre, year='2012', studio='Sunrise', added_by=user) anime.save() self.assertEqual(Anime.objects.count(), 1) self.assertEqual( unicode(Anime.objects.last()), 'anime (2012)') # using django-any class AnimeModelsTest(TestCase): def test_anime_save(self): anime = any_model(Anime, year=2012, caption='anime') self.assertEqual(Anime.objects.count(), 1) self.assertEqual(Anime.objects.count(), 1) self.assertEqual( unicode(Anime.objects.last()), 'anime (2012)')

django-any fills fields with valid data automatically:

slag = ltqltDNuEhBOEiFMmPCsdFTIhQOCiocoOykr ganre.caption = hbgZlPrrXMCQjYhxJZqKAoZCSwbboh ganre.description = ['Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, ... , natus iste explicabo aperiam laudantium?'] studio = JNVXNYwSVpuQiAyQl image = images/anime_1.jpg last_update = 2012-04-28 14:03:31.859193 added_by = XGiY

Or create your own factory:

from django.contrib.auth.models import User class UserFactory(object): counter = 0 @classmethod def create(self): """ Returns new user. """ self.counter += 1 return User.objects.create_user( username='kanata%d' % self.counter, password='kanata%d' % self.counter, email='kanata%d@mail.com' % self.counter, first_name='Kanata', last_name='Izumi')

Usage:

user = UserFactory.create()

I store factories code inside tests/factories.py file.

One more way to fill models with necessary data is fixtures. But using fixtures is a bad practice. You'll need to edit/regenerate fixture after every schema migration, this is annoying.

Using Client

Use it only if no other alternatives. Client executes a lot of code we don't want to test in this particular test. Tempate tags and filters, context processors, middlewares are examples of things to test where Client absolutely redundant.

Don't do like this:

from django.test import TestCase from django.test.client import Client class MyTestCase(TestCase): def setUp(self): self.c = Client()

self.client already available in django TestCase!

Sometimes Client can't be used and we have to find alternative ways to test our code, for example, my test for error pages:

# urls.py handler500 = 'project.apps.core.views.handler500' handler404 = 'project.apps.core.views.handler404' # views.py from django.template.loader import get_template from django.template import Context from django.http import HttpResponseServerError, HttpResponseNotFound def handler500(request, template_name='500.html'): t = get_template(template_name) ctx = Context({}) return HttpResponseServerError(t.render(ctx)) def handler404(request, template_name='404.html'): t = get_template(template_name) ctx = Context({}) return HttpResponseNotFound(t.render(ctx)) # tests.py from django.test import TestCase from django.test.client import RequestFactory from project import urls from ..views import handler404, handler500 class TestErrorPages(TestCase): def test_error_handlers(self): self.assertTrue(urls.handler404.endswith('.handler404')) self.assertTrue(urls.handler500.endswith('.handler500')) factory = RequestFactory() request = factory.get('/') response = handler404(request) self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 404) self.assertIn('404 Not Found!!', unicode(response)) response = handler500(request) self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 500) self.assertIn('500 Internal Server Error', unicode(response))

ImageField with null == False in tests

A lot of times I seen when developers save an image inside project folder, opens it and passes to form. But better way is to generate image.

This is a factory for images I use:

import Image from StringIO import StringIO class ImageFactory(object): counter = 0 @classmethod def create(self, width=200, height=200): """ Returns image file with specified size. """ self.counter += 1 image = Image.new( 'RGBA', size=(width, height), color=(256, 0, 0)) f = StringIO() image.save(f, 'png') f.name = 'testimage%d.png' % self.counter f.seek(0) return f

Or even easier way:

imgfile = StringIO('GIF87a\x01\x00\x01\x00\x80\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00ccc,\x00' '\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x01\x00\x00\x02\x02D\x01\x00;') imgfile.name = 'img.gif'

Don't forget to remove saved files from media folder:

path = my_mode_instance.image.path os.remove(path)

Patch/Mock

If briefly:

- to Patch == replace some code with some another code

- to Mock == replace some code with mock object

Mock is a black box that have every (roughly) methods and every properties we ask for. If method does not exists, mock just returns another mock instance instead this method/property. Another feature in mock is memory, it remember all interactions with it. Example:

>>> from mock import Mock >>> mock = Mock() >>> mock.some_method() <Mock name='mock.some_method()' id='4367510224'> >>> mock.some_propery <Mock name='mock.some_propery' id='4367565008'> >>> mock.some_method.call_count 1 >>> mock.some_another_method.call_count 0 >>> mock.my_method.return_value = 'Hello!' >>> mock.my_method() 'Hello!' # type help(Mock) to see all available features

In some tests there is not necessary to run particular parts of code (because their were already tested by another tests), we just need:

- method/property returns value we expected and not actually executes

- to know that method was executed specified number of times

- to know that method was executed with specified args

mock.patch allows to do patching with easy, there are two ways to use it, as decorator and as context manager:

import datetime from mock import patch from django.utils import timezone def test_some_feature(self): with patch.object(timezone, 'now', return_value=datetime.datetime(2013, 2, 27)) as mock_now: # do something

@patch.object(timezone, 'now', return_value=datetime.datetime(2013, 2, 27)): def test_some_feature(self, mock_now): # do something

Another example:

from mock import patch from google_analytics.models import GoogleAnalytics from pyga import requests from django.test import TestCase from django.contrib.sites.models import Site from .utils import ga_event @patch('pyga.requests.Tracker') def test_ga_event(self, TrackerMock): """ Check that pyga.requests.Track cals with right arguments """ analytics_code = 'UA-12345678-9' mobile_analytics_code = analytics_code.replace('UA', 'MO') sites = Site.objects.all() self.assertEqual(sites.count(), 1) site = sites[0] analytics = GoogleAnalytics.objects.create( site=site, web_property_id=analytics_code) tracker_value = requests.Tracker(mobile_analytics_code, site.domain) # this function should call pyga.requests.Tracker once ga_event('a', 'b') TrackerMock.assert_called_once_with(mobile_analytics_code, site.domain)

Not necessary to use mock.patch for patching, you can write your own context manager to patch your code:

from contextlib import contextmanager from mymodule import MyClass @contextmanager def my_patch(value=1): def f(*args, **kwargs): return value old_f = MyClass.my_method MyClass.my_method = f yield MyClass.my_method = old_f # usage: # with my_patch(value=10): # ...

Testing models

First I test __unicode__ method (just to create initial test case for model), and then add test for every new method.

Don't save data to database when testing model methods:

# Bad mymodel = MyModel.objects.create( required_field1=value1, required_field2=valued2, field3=value3) self.assertEqual(mymodel.some_method_uses_only_field3(), ...) # Good mymodel = MyModel(field3=value3) self.assertEqual(mymodel.some_method_uses_only_field3(), ...)

Testing forms

Form is a place where mistakes frequently appears, and find them with test cost much less then if user find them on production.

Form test example:

from django.test import TestCase from ..forms import ProfileForm class ProfileFormTest(TestCase): bad_test_data = [{ 'phone': '+377777777777', 'skype': 'tsukasa', 'is_valid': True, }, { 'phone': '+077777777777', 'skype': 'tsukasa', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+077777aaaa77', 'skype': 'tsukasa', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+077777aaaa77', 'skype': 'tsukasa', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+377777777777', 'skype': 'ui', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+377777777777', 'skype': '1tsukasa', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+377777777777', 'skype': 'tsukasa!', 'is_valid': False, }, { 'phone': '+377777777777', 'skype': 'tsukasa ' * 6, 'is_valid': False, }] def test_profile_form(self): """Phone number have to start from +3... Skype name must contains 6 to 32 characters, start from letter and contains only letters and numbers""" for data in self.bad_test_data: profile_form = ProfileForm(data) self.assertEqual(profile_form.is_valid(), data['is_valid'])

Testing context processors

Use RequestContext:

from django.template import RequestContext from django.test.client import RequestFactory factory = RequestFactory() request = factory.get('/') context = RequestContext(request) self.assertIn('MyVar', context)

Testing middlewares

Create request using RequestFactory and pass it to middleware.

Or create mock and pass it to middleware instead request.

from django.test.client import RequestFactory from .middlewares import MyMiddleware factory = RequestFactory() request = factory.get('/') middleware = MyMiddleware() middleware.process_request(request)

Also you can check that middleware was included to MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES settings variable.

Testing template tags

from django.template import Template, Context template = Template('{% load 'myapp_tags' %}{% mytag %}') context = Context({}) result = template.render(context) self.assertEqual(result, ...)

Testing template filters

Think about it like about function:

from .templatetags.myapp_tags import myfilter result = myfilter(somearg) self.assertEqual(result, ...)

Testing management commands

Use call_command to execute command.

Use StringIO to obtain stdout/stderr.

from StringIO import StringIO from django.core.management import call_command out = StringIO() err = StringIO() call_command('somecommandname', stdout=out, stderr=err) ...

Have fun writing tests!

Tests are the Programmer's stone,

transmuting fear into boredom.